Breaking News

Popular News

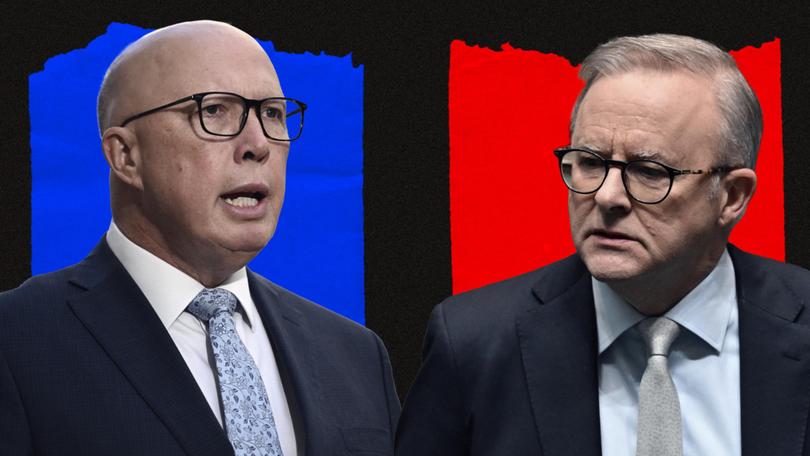

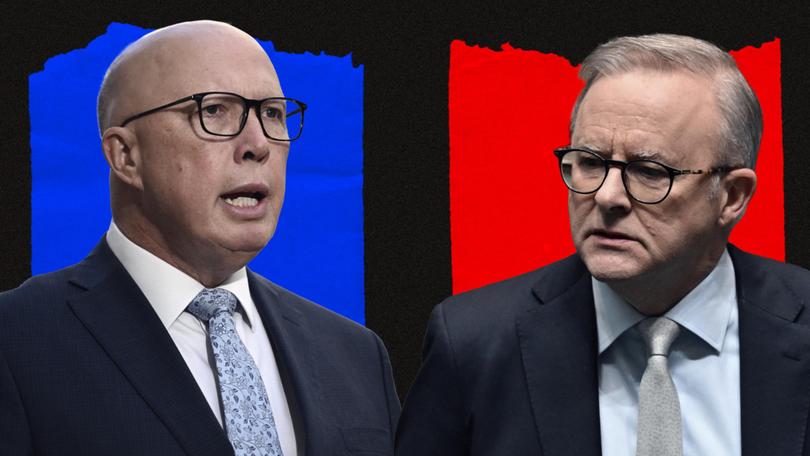

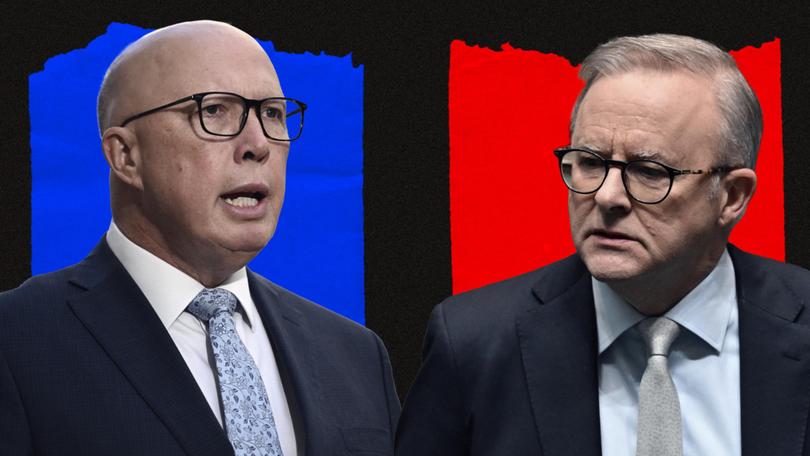

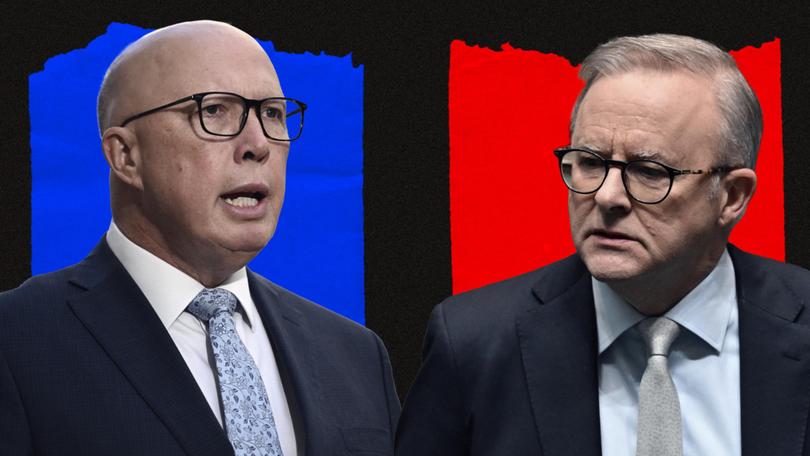

Sydney – Prime Minister Anthony Albanese this week declared war on supermarket “price gouging,” bluntly accusing major grocery chains of “taking the piss” out of Australian consumers. In a sharp opening salvo of the 2025 election campaign, Albanese promised that a re-elected Labor government would outlaw excessive pricing in the grocery sector by the end of the year.

Drawing on the Treasury, the ACCC and other experts, a new task force would devise an “excessive pricing regime” enforced by the competition watchdog, with “heavy fines” on supermarkets that rip off consumers. It’s a bold pledge to tackle a cost-of-living crisis, but it also echoes Australia’s past experiments in price oversight.

As some might put it, we’ve seen this play before. To understand where this policy might lead, it’s worth revisiting the Prices Surveillance Act 1983, a legacy of the Hawke era, and asking what lessons it holds for today.

When Bob Hawke’s Labor government came to power in 1983, Australia was under stagflation – stagnant growth, high inflation, and high unemployment. Inflation was running in the double digits, and joblessness neared 10%.

The country had just endured a recession in 1982 and needed to break an earlier price spiral. Hawke’s mission was to tame inflation without another economic collapse. Fast-forward to the 2020s: Australia has been hit by the highest price surge in over 30 years after decades of low inflation, peaking at 7.8% annual CPI inflation in late 2022.

Grocery bills, power prices and rents have all climbed sharply, squeezing household budgets. The Reserve Bank’s response has been aggressive interest rate hikes – effectively “making people unemployed” to curb demand – but political leaders are under pressure to find more direct remedies as voters struggle with cost-of-living pain.

In the 1980s, the centrepiece of Hawke’s anti-inflation strategy was not just monetary policy but a grand bargain with unions: the Prices and Incomes Accord. Unions agreed to restrain wage demands in exchange for the government addressing social wage issues (like Medicare) and keeping a lid on prices. Part of that deal was creating a price-monitoring body to show that companies, not just workers, were doing their part to fight inflation.

Hawke didn’t want a heavy-handed price freeze – Australians had twice rejected referendums to give Canberra sweeping price-control powers in 1948 and 1973. Instead, Labor opted for a subtler oversight mechanism. This was the genesis of the Prices Surveillance Act 1983.

By contrast, today’s inflation has different underpinnings. It’s not a 1970s-style wage-price spiral; wage growth remains modest. Instead, supply shocks from the pandemic and war, a productivity slump, and rising profit margins have been blamed for “excess” inflation. Research indicates that about two-thirds of the above-target inflation since 2019 has come from higher corporate profits, which have far outpaced labour cost contributions.

In plainer terms, many companies have been able to expand their profit margins under cover of inflation, a phenomenon some dub “reflation.” The ACCC’s recent grocery sector inquiry bolsters that view: it found Coles and Woolworths raised prices during the COVID-era cost-of-living crisis beyond what higher costs warranted, fattening their profits.

The big two supermarkets (plus Aldi) now rank among the most profitable supermarket businesses in the world, commanding an oligopoly that the regulator says needs reform. With households feeling like price-takers at the mercy of a duopoly, the political appetite for intervention has returned.

The Prices Surveillance Act 1983 (PSA) was the Hawke government’s answer to inflationary pricing. It replaced Gough Whitlam’s more hardline Prices Justification Tribunal (PJT), which, in the 1970s, forced big companies to pre-justify any price hikes and often delayed them in suppressing inflation. Hawke scrapped the PJT in mid-1983 and established the Prices Surveillance Authority (PSA) under the new Act as part of the first Accord with the unions.

This move was largely symbolic and political – “a sop to the unions” to show that while wages were being restrained, the government would also keep an eye on business pricing. The PSA’s first chair, Hilda Rolfe, and later Allan Fels (appointed 1989), were tasked with promoting competitive pricing and restraining excessive price rises in markets where competition was weak.

In practice, the PSA was a relatively toothless tiger. It could “declare” certain goods or services for price surveillance, requiring the companies involved to notify the PSA (later the ACCC) of any proposed price increases. The idea was to shine sunlight on pricing decisions and allow the regulator to examine if increases were justified.

But the Act granted no power to outright block or roll back prices – compliance was essentially voluntary. One review dryly noted that “moral suasion through publicity, and the threat of the minister initiating an inquiry, are the principal enforcement mechanisms” under the PSA. In other words, the PSA could investigate and expose possible price gouging and ask companies to show restraint, but it couldn’t directly slap penalties or impose price caps on a whim.

Through the late 1980s and 1990s, the PSA’s scope narrowed. Initially, it scrutinized some high-profile sectors (for example, petroleum or telecommunications prices were periodically reviewed), but Australia embraced market reforms and deregulation over time. By the 1990s, only a few “declared” monopoly-like services remained under formal price notification – postal stamps, airport fees, or harbour towage charges. The PSA (as an agency) was merged into the newly formed ACCC in 1995 amid National Competition Policy reforms.

Price oversight became just one of many ACCC roles, a minor one. Inflation had subsided – dropping to ~5% in the mid-80s and staying low in the 90s – thanks mainly to the Accord and tight monetary policy (and arguably a dose of recessionary medicine). The need for an expansive price watchdog seemed to wane.

Did the PSA achieve its goals? Only partially. It likely had a modest chilling effect on price hikes in some sectors simply by existing – companies knew egregious increases could prompt a public inquiry and bad press. Allan Fels, who headed the PSA and then the ACCC, became adept at wielding this “name and shame” power. During the introduction of the GST in 2000, when the Howard government tasked the ACCC to prevent businesses from using the new tax as cover for sneaky price jumps, Fels turned public exposure into a powerful deterrent.

No company wanted to be branded a price-gouger on the evening news. As one commentator put it, by the early 2000s, Fels had become “a price control referendum in human form,” using the media to do what his limited enforcement powers could not. However, beyond such high-profile episodes, the PSA framework was far from a panacea.

A Productivity Commission review in 2001 found the Act lacked clear objectives and overlapped with other regulatory tools, calling it a “last resort” instrument with several deficiencies. Even the ACCC acknowledged that formal price notification was a cumbersome, imperfect substitute for genuine competition, suitable mainly for former public monopolies where other pro-competitive reforms weren’t feasible.

Ultimately, the PSA outlived its political usefulness. In 2004, the Howard government repealed the Prices Surveillance Act amid prevailing free-market sentiment and very low inflation. The remaining price oversight functions were folded into Part VIIA of the Trade Practices Act (now the Competition and Consumer Act). In essence, when directed by the government, the ACCC kept limited powers to monitor or hold inquiries into prices in specific industries.

Still, the era of a standing price-watchdog law was over. Australia would rely on competition (where it existed) and general prohibitions on collusion or misuse of market power to keep prices in check – and leave broader inflation control to the Reserve Bank. From 2004 until very recently, the official line was that charging “unreasonably high” prices is not illegal as long as there’s no anti-competitive conduct. The ACCC could act on cartels or misleading pricing, but simply “watching or worrying about prices” was no longer its mandate.

Now, the pendulum is swinging back. Albanese’s proposed crackdown on supermarket price gouging is the decade’s most significant federal pricing intervention talk. So, what exactly is Labor promising to do? In no-nonsense terms, they want to give the ACCC some real teeth to bite down on supermarkets that jack up prices unfairly.

Albanese’s rhetoric in announcing these moves was unusually colourful for a PM. He cited a European definition of price gouging as a price “unfair and excessive” with no reasonable relation to the product’s economic value, then translated it into plain Australian: “Price gouging is when supermarkets are taking the piss out of Australian consumers… Everyone else knows it. Consumers know. We’ll take action.”

It was a populist flourish, underscoring that this is about fairness at the checkout – ensuring, as Treasurer Jim Chalmers put it, that Australians aren’t treated like “mugs” by big grocers.

However, turning that tough talk into effective policy is easier said than done. Even Albanese acknowledges there’s “no silver bullet” for the complex factors driving grocery prices. That’s why the ACCC is tasked to consult and design the excessive pricing framework.

Questions abound: How do you precisely define “excessive” pricing in a legal sense without simply freezing prices? Do you peg it to some measure of costs plus a reasonable margin or compare Australian prices internationally?

Who decides what profit margin crosses the line from acceptable to exploitative? These details will matter immensely. For now, the government has essentially kicked this can to the experts – a decision the opposition slams as dithering.

Liberal senator James Paterson argued Labor had created its “fifth committee or review into supermarket prices” instead of acting, calling the policy “insulting” and asking why, if it’s such a good idea, Labor “didn’t do it three years ago” when they first took office. In short, why the wait? It’s a fair critique – cost-of-living pressures have been mounting throughout this term, yet only on the eve of an election is the government moving to outlaw gouging.

So, is Australia about to dust off the old playbook of price oversight? In some ways, yes – but with a modern twist. The Albanese government’s plan revives the spirit of the Prices Surveillance Act while trying to fix its flaws. It’s instructive to compare the two approaches:

Scope: The original PSA was economy-wide in theory but became focused on select industries (mostly monopolies or government enterprises). Labor’s new plan is narrowly targeted at the grocery sector, at least for now. This targeted scope might make it more manageable – regulators can deep-dive into supermarket pricing dynamics (from farm gate to shelf) rather than policing everything under the sun.

Teeth: As noted, the PSA relied on moral suasion; it could delay and shine a light but not directly punish high prices. The new regime intends to give ACCC real enforcement power, presumably civil penalties, for defined price gouging behaviour. This is closer to European competition law, where, in rare cases, a dominant firm can be prosecuted for “excessive pricing.” Albanese is essentially seeking to arm the ACCC with a stick it never honestly had before: the ability to say, “That price is too high,“ and back it up with fines or other orders. That’s a significant policy shift.

Political Intent: Both then and now, a Labor government is responding to public anger about rising prices. In the 80s, it was about aligning with the unions and fighting inflation; today, it’s about protecting consumers (and voters) from corporate profiteering during tough times. The through line is a philosophy that market forces sometimes need a referee. As ACCC’s deputy chair, Mick Keogh, said, stronger oversight may be required to “deliver better consumer outcomes” when competition is weak. The supermarket duopoly, controlling roughly 67% of grocery sales, is the market where traditional competition isn’t delivering outstanding results for shoppers – hence the call for a watchdog role.

Risks and Limits: Any price regulation risks unintended consequences. The PSA’s gentle approach largely avoided disrupting markets, but one could argue it also avoided truly correcting them. If miscalibrated, a stricter law against excessive pricing could discourage retailers from discounting less profitable lines or lead to gaming of what costs are included in “reasonable” prices. Critics on the free-market side will warn that governments shouldn’t be in the business of setting prices – let competition (or new entrants) solve it. But competition takes time to materialize (and, in some sectors, may never flourish without intervention). On the other hand, consumer advocates might say this plan doesn’t go far enough – companies might pay fines as a cost of doing business without the ultimate threat of breaking up a monopolist. There’s also the chance that supermarkets, under intense scrutiny, pull back on some price increases in the short term (a win for consumers) but try to wait out the political storm.

Do we need a 2025 version of the Prices Surveillance Authority, armed with actual bite, not just bark? Some experts, like veteran finance commentator Alan Kohler, have argued it’s “time to revisit the Fels system of price control” – meaning a dedicated effort at price surveillance and public shaming of gougers to complement interest rate policy.

In Kohler’s view, leaving all the inflation-fighting to the Reserve Bank has proved inadequate when companies are hiking prices simply because they can. A modern PSA could systematically track prices in concentrated sectors (supermarkets, banks, energy, etc.) and call out unjustified rises. This is basically what the ACCC just did with groceries in its report – but only after being asked. Making it a permanent, institutional role could keep pressure on oligopolies continuously.

The government’s plan aligns somewhat with that philosophy, though they haven’t announced a new standalone Authority. Instead, they’d use the AC. It’s worth noting that overseas models are being examined: many European countries have laws against exploitative pricing during emergencies; the EU and UK have considered tighter rules on dominant firms’ pricing practices.

Albanese mentioned that 30 U.S. states have laws against price gouging, typically triggered during natural disasters or abnormal market disruptions. Those laws often define gouging as raising prices by more than a certain percentage during a declared emergency. Applying that concept to everyday supermarket operations is novel. It would set an interesting precedent among advanced economies if Australia pulls it off.

One thing is sure: public sentiment is firmly behind the action. Australians have been through two years of real incomes going backwards. They hear Coles and Woolworths enjoy bumper profits and generous shareholder payouts while their grocery bills break records.

The ACCC confirmed shoppers’ suspicion that some price rises have been feeding profits, not just covering costs. In this climate, even free-market purists in politics concede the need for intervention. “We’d be delighted to make price gouging illegal,” said the opposition’s Paterson while arguing Labor was late to the party. The debate now is not whether to act on price gouging but how.

Let’s cut through the spin: Is the Albanese government’s plan a genuine solution or just election-year theatre? Historically, Australia’s attempts to police prices have been, as one observer put it, a “long and futile history” of good intentions running into complex economic realities.

The Prices Surveillance Act of 1983 was born of a specific time and compromise; it quietly faded as time passed. Today’s cost-of-living crisis presents a new challenge and perhaps a chance to correct past mistakes. A modern price oversight regime – one that can penalize egregious profiteering – might succeed in reining in corporate excess, provided it’s used judiciously. It must be transparent, evidence-based, and paired with efforts to boost competition (so that price controls don’t become a permanent crutch).

Labor’s plan to empower the ACCC is to recognise that “nobody is watching prices” right now except the central bank. It’s a bet that more intelligent regulation can fill that void without sliding into heavy-handed meddling. If it works, Australian families could finally see relief at the checkout. If it fails – whether through loopholes, lack of will, or unintended fallout – we’ll have added one more chapter to the futile history and the cost of living will remain the defining political battle.

One thing is for sure: the watchdog is waking from its slumber. Supermarket CEOs might be wise to voluntarily dial down their margins now because public tolerance for “taking the piss” has run out. As we weigh new laws against lessons from 1983, a timely reminder to hold power to account applies equally to governments and corporations. Both must be kept honest to ensure Australians get a fair go at the checkout.

Sources:

• https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2025/mar/29/labor-promises-price-gouging-crack-down-on-supermarkets

• https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2025/mar/21/accc-report-supermarkets-coles-woolworths-aldi

• https://www.9news.com.au/national/federal-election-2025-prime-minister-anthony-albanese-announces-tough-crackdown-on-supermarket-price-gouging/1c17d070-5a99-4364-a4c9-431fda60de99

• https://www.thenewdaily.com.au/finance/2023/06/22/price-control-inflation-alan-kohler

• https://www.pc.gov.au/inquiries/completed/prices-surveillance-act/report (Productivity Commission Report, 2001)

• https://www.accc.gov.au/system/files/Issues%20paper_0.pdf (AC Issues Paper, 2004)

• https://www.uts.edu.au/news/business-law/does-australia-need-another-prices-and-incomes-accord

• https://www.moneymag.com.au/inflation-hits-78percent-so-has-it-peaked

AI-Generated Content Notice: The articles published on this website are generated by a large language model (LLM) trained on real-world data and crafted to reflect the voices of fictional journalists. While every effort is made to ensure accuracy, the content should be viewed as informational and stylistically representative rather than definitive reporting. Always verify the information presented independently. Read our full disclaimer by clicking here.